Projection Will Never Be As Good As Physical Scenery

A discussion on why that argument misses the point.

I often hear the phrase “Projection will never be as good as physical scenery” and it grinds on me like an amateur lighting op discovering the strobe button for the first time. It’s a rash statement, and like most rash statements, it misses the point entirely.

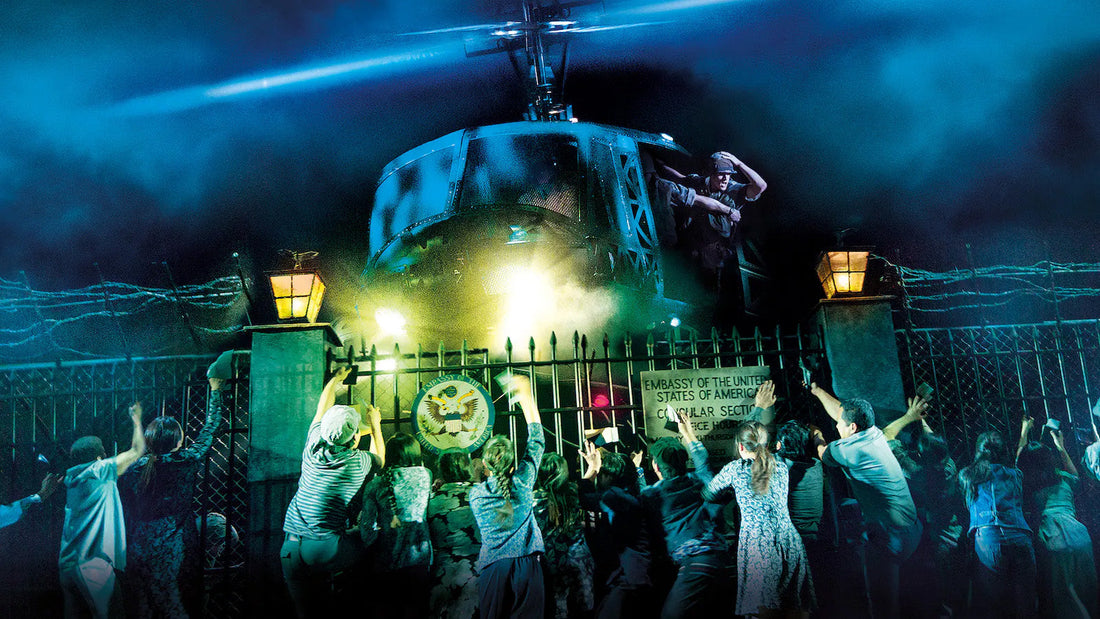

No one’s suggesting we tear down all the flats, torch the props, and turn every production into a PowerPoint presentation. Projection was never meant to replace traditional scenery and why would it? Almost everyone I know working in the industry started in theatre surrounded by timber, paint pots, and papier-mâché. Of course we love physical sets. We were raised on them. We swooned over crashing chandeliers in Phantom, gasped at the rotating barricade in Les Mis, and had our minds blown by the Huey helicopter punching through the ceiling in Miss Saigon.

If you told me we were replacing that with a screensaver of a helicopter, I’d walk straight into the orchestra pit.

But that’s not what’s happening. Projection isn’t a replacement. It’s an experiment. It’s an addition. It’s another storytelling tool in our toolbox, right next to the paintbrush, the staple gun, and the “hope this set survives the bump-in” prayer.

A 90s Theatre Kid with a Floppy Disk and a Dream

Growing up in the 90s, I was lucky enough to have a computer in the house. While other kids were hand writing their homework, I was creating the most hideous slide transitions in PowerPoint. (And yes, I’m old enough to remember when you had to print your PowerPoint slides onto a transparencies to use on overhead projectors. Ancient tech historians, take note.)

I’ve always loved technology. I never saw it as cheating, I saw it as a tool. A tool that helped me work faster, test ideas quicker, and save trees by not starting from scratch every time I changed my mind about a colour scheme.

At 15, our school took us to a production that used projection for its entire set. It wasn’t perfect, but it was bold. It was trying something new. I left inspired. My drama teacher left unimpressed. He said, “We might as well have gone to the cinema.” He meant it as a burn. I still don’t understand the scorn. Popcorn’s great.

That kind of resistance followed me throughout my training. When I started designing for theatre in 1998, I did everything on the computer and trust me, in 1998, that was not cool. (Neither were my frosted tips, but let’s stay on topic.) My designs were compared to hand-drawn work and often dismissed as less authentic, less artistic. And look, I adore hand-drawn work. I admire the artists who can make a pencil do magical things. I just knew I could do more, faster, and better using the tools that worked for me. And those tools had USB ports.

Even during my undergrad, computer-aided design felt like a second-class citizen. We were still using halogen fixtures and slide projectors in my first year. By third year, we’d seen a few LED lights and a data projector or two, but the curriculum hadn’t quite caught up. I later returned to study a postgrad and found the same weird bias: technology was still seen as “lesser.” At that point, I’d had enough. I leaned in. If I was going to be the tech nerd in the room, I was going to own it.

Projection isn't Replacement, it's Possibility.

What I’m trying to say is: the resistance I saw to computers and tech in theatre in the late 90s and early 2000s is the same pushback we’re seeing now with projection. The fear that something new is going to take away jobs or tradition or meaning.

But projection isn’t a threat, it’s an opportunity. It’s not here to take your flats and fly bars. It’s here to offer new possibilities for storytelling. Does projection look like traditional scenery? No. But that’s the point. It can do things that paint and plywood can’t. It can evolve in real time. It can transport an audience in a blink. It can, when used right, feel like magic.

Is it always perfect? Nope. Sometimes it flops. But that’s the fun part, we’re in the experimental phase. We get to try new things, fail gloriously, and try again. Theatre thrives on risk, and projection is just another form of creative risk-taking.

What StageScape Projections Offers

At StageScape, we work with schools and theatre companies that don’t have the time, money, or people-power to build complex scenery. We’re not offering projection as a magic bullet, we’re offering it as a practical solution. A way to create immersive, high-quality storytelling without needing a workshop full of sawdust and a truckload of flats.

Even our full Beauty and the Beast package isn’t projection-only. It includes suggested physical elements like a village fountain, a Beast’s armchair, and a dining table for Be Our Guest. Projection is the backdrop but physical props still have a place on the stage.

We don’t believe projection should replace physical scenery. We believe it should work with it. The best results come when the two are used together. Each strengthens the other. And sometimes, yes, projection is the more practical choice. Especially when you're trying to stage a show with the production value of a Broadway show on a small stage.

A Brilliant Example: Miss Saigon

Let’s circle back to Miss Saigon. The original production had a full-scale helicopter descend onto the stage. Iconic. Later versions used projection instead - not quite as jaw-dropping, but still impactful. But the 2023 Melbourne production? It used both. It started as projection, then transformed into a physical helicopter mid-scene. It actually got applause. Applause for a set piece. That’s when you know it works.

That’s the future I see for projection. Not a replacement, but a partner. A compliment. A collaborator.

So let’s stop being scared of this new technology. Let’s stop pretending projection is some pixelated threat to the legacy of theatre. Let’s play. Let’s experiment. Let’s try things. Some of them will be rubbish. Some of them will be glorious. That’s theatre.

And for the record, if anyone tells me projection “isn’t real theatre,” I’ll project a 6 metre eye-roll onto the cyclorama. In high definition.